Using life science to create high-value products from marine residuals

Published 9 Mar 2023 (updated 29 Oct 2025) · 5 min read

Norwegian life science companies are finding innovative new ways to extract crucial compounds from marine residual materials,

leading to key innovations in health, medicine and food production while building a robust blue circular economy.

In terms of mass, as much as 35 per cent of the harvest from fisheries and fish farms is residual materials.

These are biological “leftovers” after the primary product has been extracted – for example, skin, guts, heads and bones from fish and shells from shellfish.

“Both aquaculture and pelagic fisheries create a high volume of residual material,” states Hanne Mette Dyrlie Kristensen, VP Investor Relations, Business Development and Collaboration at The Life Science Cluster.

“For example, only about two thirds of a salmon’s weight can be sold as fillets.”

“The question is: What do we do with the rest? Do we throw it back into the ocean, sell it as pet food, or can we find new, higher value uses for it?”

Hanne Mette Dyrlie Kristensen

Using marine residuals to forge a blue circular economy

Norwegian companies are already adept at preventing marine residuals from going to waste. A whopping 82 per cent of the harvest from Norwegian fisheries and fish farms is already being utilised in one way or another. Nevertheless, Kristensen would like to see an even higher percentage.

“We want to increase the use of marine residuals because it is a way of ensuring sustainable and circular resource use. Making sure we use every ounce we harvest is also a way of showing respect for marine life.”

Enter the life sciences.

Norway is a global leader in “blue” life science

“The life science sector is developing solutions to the world's biggest challenges and helping us to achieve the UN Sustainable Development Goals,” says Kristiansen.

She points out that Norway’s life science sector has one unique advantage: synergies with the marine sector. Norwegian waters are teeming with fisheries and fish farms, and the seafood industry is Norway’s second largest exporter.

“Compared to the rest of Europe, the Norwegian life science sector is very ‘blue’ – that is we have a unique grounding in and connection to marine industries,” she says.

“We are fortunate to be closely connected to a booming marine sector. This puts us in a unique position to create value from untapped marine resources.”

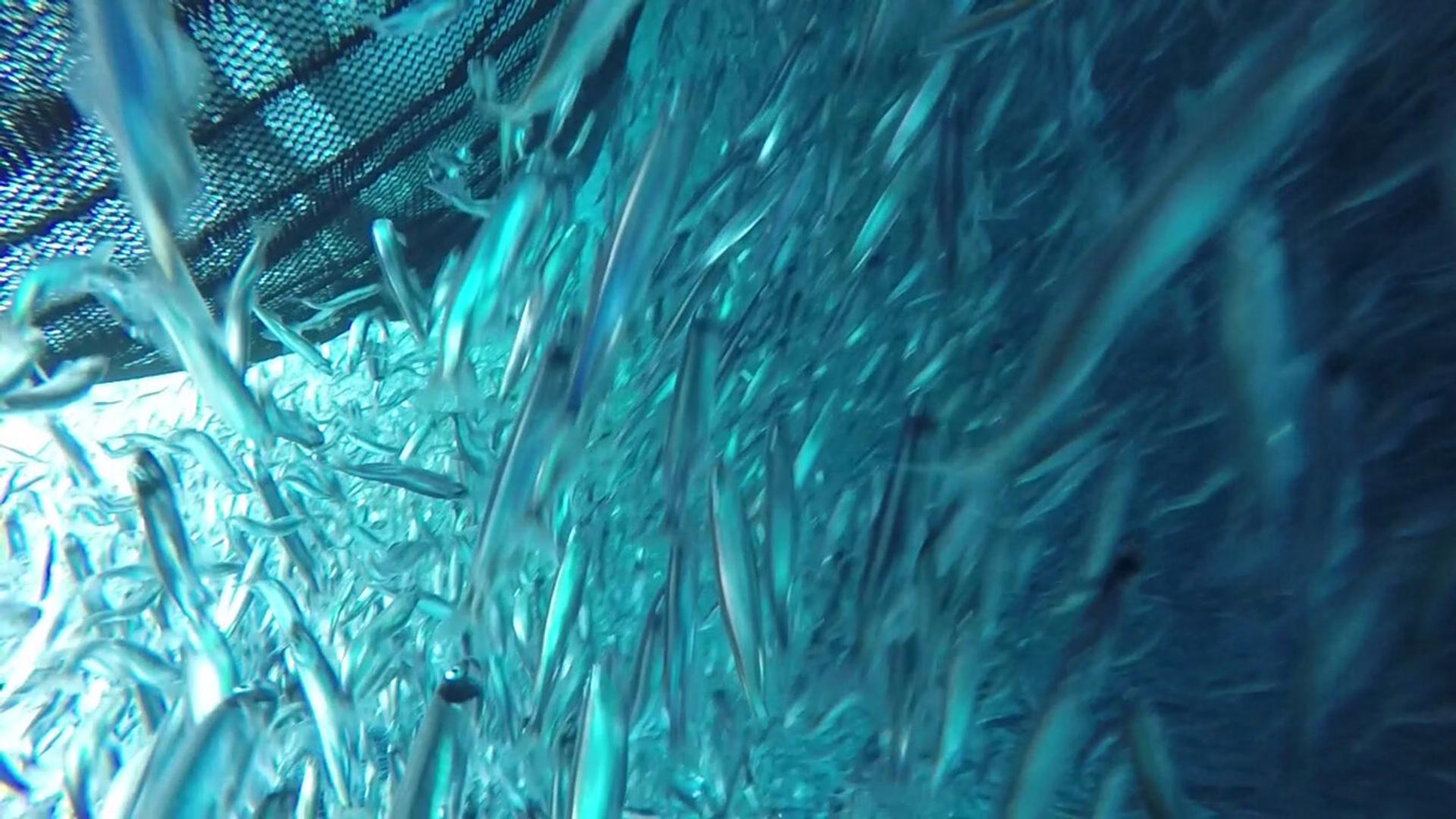

Arctic Bioscience produces high-DHA phospholipid extract from sustainable herring roeRomega™ from Arctic Bioscience is a caviar oil rich in omega-3 phospholipids extracted from herring roe, a side stream from herring fisheries.

Arctic Bioscience produces high-DHA phospholipid extract from sustainable herring roeRomega™ from Arctic Bioscience is a caviar oil rich in omega-3 phospholipids extracted from herring roe, a side stream from herring fisheries. Marealis bioactive marine peptides from prawn shells improve blood pressure healthAfter a decade of research, Norwegian biotech Marealis has developed a sustainable natural health product to prevent and treat elevated blood pressure, derived from previously discarded prawn shells.

Marealis bioactive marine peptides from prawn shells improve blood pressure healthAfter a decade of research, Norwegian biotech Marealis has developed a sustainable natural health product to prevent and treat elevated blood pressure, derived from previously discarded prawn shells. Aker BioMarine harnesses the nutritional power of krillAker BioMarine is the world’s leading supplier of krill, a natural, renewable source of nutrients from the waters of Antarctica. “Our purpose is to bring more sustainable food into the world for human, animal and planetary health,” says Pål Skogrand, VP Policy and Impact at Aker BioMarine.

Aker BioMarine harnesses the nutritional power of krillAker BioMarine is the world’s leading supplier of krill, a natural, renewable source of nutrients from the waters of Antarctica. “Our purpose is to bring more sustainable food into the world for human, animal and planetary health,” says Pål Skogrand, VP Policy and Impact at Aker BioMarine.

Using marine technology and biotech for “blue” health

Many products can be made from marine residuals. Kristensen explains that Norwegian companies are continuously discovering untapped potential and drawing on synergies between industries. Nowhere is this more visible than in the area of blue health.

“A good example is Arctic Bioscience, a company that uses herring roe to extract useful compounds for pharmaceuticals and nutritional supplements. Herring roe is a new resource in this respect; it was previously discarded completely during the processing of herring.”

Meanwhile, Marealis has developed PreCardix – the world’s first bioactive marine peptides clinically proven to lower blood pressure. PreCardix contains some unique bioactive peptides derived from the proteins of fresh, cold-water Arctic prawn shells (Pandalus Borealis). This proprietary technology allowed PreCardix to leverage the prawn shell waste, and create a potent, natural blood pressure solution.

Innovations in blue health are not limited to marine residuals, but also extend to previously untapped species. Aker BioMarine, for instance, uses low and zero-emission technology to fish in Antarctic waters for krill, a tiny protein-rich crustacean regarded as a renewable resource.

As the world’s leading supplier of krill, Aker BioMarine covers the entire supply chain from certified sustainable harvesting to production, and its krill-based ingredients are sold for use in aquaculture, animal feed and human nutritional supplements.

Similarly, Zooca, based in North Norway, sustainably harvests Calanus finmarchicus, the world’s most abundant species of zooplankton and one of the Norwegian Sea’s largest renewable resources. The company manufactures supplements rich in fatty acids for human health and nutrition as well as premium ingredients for aquaculture feed.

Beyond omega-3: Superior lipid extract for human health and nutrition from a sustainable marine resourceZooca® – The Calanus® Company has developed and produces Zooca® Calanus® Oil, a novel bioactive fat that is more than just an omega-3. With a full-spectrum fatty acid profile, Calanus® Oil contains more than 40 different fatty acids bound in their natural form.

Beyond omega-3: Superior lipid extract for human health and nutrition from a sustainable marine resourceZooca® – The Calanus® Company has developed and produces Zooca® Calanus® Oil, a novel bioactive fat that is more than just an omega-3. With a full-spectrum fatty acid profile, Calanus® Oil contains more than 40 different fatty acids bound in their natural form. Zooca® produces superior aquaculture feed ingredients from renewable marine resourceZooca® – The Calanus® Company produces superior feed ingredients from the zooplankton Calanus finmarchicus – the Norwegian Sea’s largest renewable and harvestable resource. The ingredients are tailored for aquaculture species and have shown to have a positive impact on growth, health and survival.

Zooca® produces superior aquaculture feed ingredients from renewable marine resourceZooca® – The Calanus® Company produces superior feed ingredients from the zooplankton Calanus finmarchicus – the Norwegian Sea’s largest renewable and harvestable resource. The ingredients are tailored for aquaculture species and have shown to have a positive impact on growth, health and survival.

Healthy fish mean high-quality residual materials

Kristensen also sees an opportunity for Norway to use marine-based life science to enhance its export potential in other sectors.

“Norway has an ambitious target of increasing seafood exports fivefold by 2050. For this to happen, we need to innovate in areas such as the quality of aquaculture feed, which impacts fish health and welfare. We see promising developments in using marine residuals and residuals from other sectors. In that sense, there’s a double benefit to be gained: we promote the circular economy while potentially increasing the quality and sustainability of our aquaculture sector.”

In this undertaking, Norway can build on another advantage: the high quality of its raw materials.

“Speaking of the aquaculture sector: Norwegian fish farms have the lowest rate of antibiotic use in the world. This is due in good part to the Norwegian company Pharmaq, which develops vaccines for fish. Globally, seven of 10 vaccinated farmed fish are vaccinated with Pharmaq vaccines.

Another Norwegian company that is developing solutions to improve the health and welfare of farmed fish, while improving the quality of the final product is STIM. It has developed a solution to battle harmful Yersinia bacteria, which cause disease in production fish and can only be cured with antibiotics. The company uses bacteriophages – naturally occurring viruses that target specific bacteria without affecting the fish’s microbiome – in its groundbreaking, environment-friendly product.

“The upshot,” says Kristensen, “is that not only are Norwegian fish products of high quality, but so are the products from fish residuals.”

Bioretur converts fish waste to fertiliserBioretur provides land-based and closed aquaculture facilities with treatment plants and services to convert fish sludge to fertiliser and other usable resources.

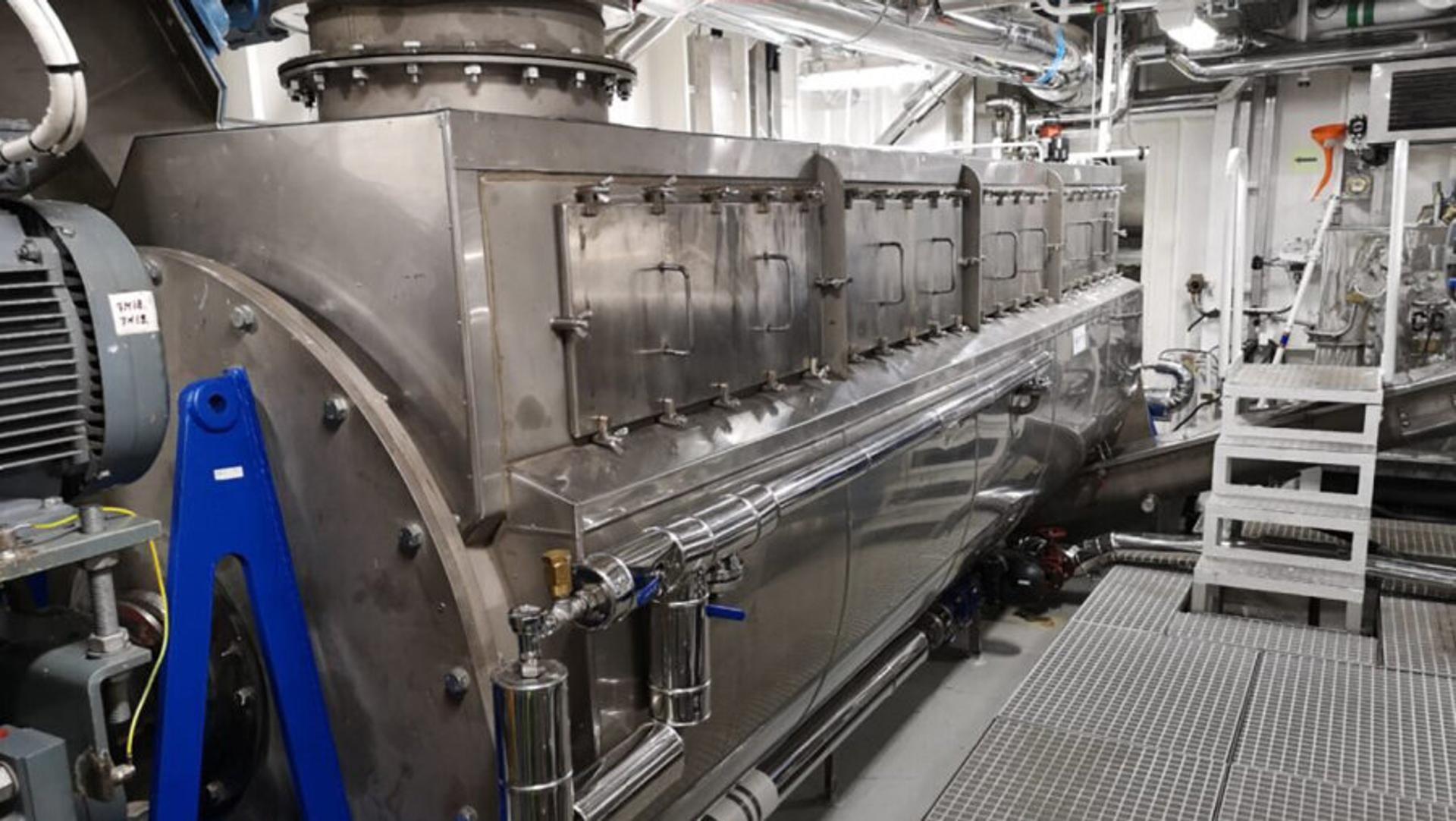

Bioretur converts fish waste to fertiliserBioretur provides land-based and closed aquaculture facilities with treatment plants and services to convert fish sludge to fertiliser and other usable resources. AMOF-Fjell fishmeal plant turns trawler waste into profitable fish productsThe AMOF-Fjell fishmeal plant converts fish waste to valuable nutritional products on board fishing trawlers. “The world needs more marine protein and nutrients. Our compact plant helps to increase the yield of these much-needed products,” says Ørjan Jansen, Project Manager at AMOF-Fjell Process Technology.

AMOF-Fjell fishmeal plant turns trawler waste into profitable fish productsThe AMOF-Fjell fishmeal plant converts fish waste to valuable nutritional products on board fishing trawlers. “The world needs more marine protein and nutrients. Our compact plant helps to increase the yield of these much-needed products,” says Ørjan Jansen, Project Manager at AMOF-Fjell Process Technology.

Creating new marine exports to replace oil and gas

The Life Science Cluster works closely with marine business clusters such as NCE Blue Legasea, which focuses on wild-caught marine raw materials, and Biotech North, which focuses on blue biotech, to build new and sustainable value chains with marine resources.

“Together, we are able to support development of new opportunities for using marine residuals in the life science sector,” she says.

The cluster is also working with regulators to pave the way for new life science-based value chains, including marine value chains.

“This is a field where things move fast. We are in a position where the industry is coming up with products that no one had thought about when the rules and regulations were made. As clusters, we have to engage actively with the regulatory framework, working with both Norwegian and European authorities to adapt the framework as the technology progresses and we find new uses for marine residuals.”

In spite of regulatory hurdles, Kristensen is optimistic.

“As a country, we must think long term about replacing our main exports, oil and gas. Although no single industry will become ‘the new oil’, I believe the Norwegian life science sector has significant potential for growth and job creation,” she concludes.