Versatile Norwegian wood grows in sustainable uses

About one-third of Norway is forested, and 43 per cent of its productive forest area is mature trees, ready for harvest. Almost all Norwegian forest land is certified sustainable by the PEFC, a global NGO. Only Finland and Sweden can rival Norway’s forest health.

Norwegian forests are filled with Norway spruce and Scots pine, two of the most durable trees on the planet. Their durability comes in part from the cool Scandinavian climate, which naturally increases tree density. When paired with technology such as glue-laminated timber, Norwegian wood can be used to build structures such as airports, sports halls and bridges.

“Norway has an abundance of timber. We have the capacity to harvest many more trees without negatively impacting the ecosystem. Our excellent forest management over many years has made this possible.”

Krister Moen

Specialist in Bioeconomy and Building, Innovation Norway

Versatile renewable resource

Norwegian wood is versatile as well. “In theory, anything made from petroleum can be made from wood,” says Hans Asbjørn K. Sørlie, Director of Forestry and Environment at the Norwegian Forest Owners’ Federation. In this regard, Norwegian companies are breaking new barriers every day.

A good example is Borregaard, one of the world’s most advanced biorefineries. Borregaard uses wood components to produce eco-friendly biochemicals that can replace oil-based products for sectors ranging from agriculture, aquaculture and construction to pharmaceuticals, cosmetics and batteries. The company even makes the world’s only wood-based vanillin, which has a 90 per cent lower carbon footprint than vanillin synthesised from crude oil.

Along similar lines, Glommen Mjøsen Skog will soon build a manufacturing facility for wood molasses for use in animal feed. In addition, Norske Skog delivers CEBICO, a compound material made of wood pulp fibre and thermoplastic that reduces the carbon footprint of finished plastic products.

Treklyngen prioritises circularity in wood

Just north of Oslo, the Treklyngen industrial park offers an eco-friendly home base for wood innovators. “Our core focus is biofuels, biocarbons and advanced processing techniques within wood fibre. Plus, we’ve added anything that has any kind of synergy with our core strategy, specifically data centre operations,” says Rolf Jarle Aaberg, CEO of Treklyngen.

Treklyngen provides four hydropower plants for clean energy, reuse of waste heat from data centres and other industries, and easy access to water for industrial process and cooling needs. A rail terminal and close proximity to a metro area, international airport and harbour keep transport costs and emissions down. Skilled labour is readily available from the Oslo region.

“We welcome international companies that want to expand their global outreach from a Norwegian base.”

Rolf Jarle Aaberg

CEO Treklyngen

Global energy giants get involved

Treklyngen hosts several promising bioenergy projects. One of them is BioJet, a Norwegian biofuels company that plans to convert forestry and wood-based construction waste into lower-emissions biofuels. Recognising opportunity, ExxonMobil recently acquired a 49.9 per cent stake in BioJet.

Another Treklyngen resident is Vow Green Metals, which will produce biocarbon for the metallurgy industry, CO₂-neutral gas for heating and biofuel for the petrochemical industry. In addition, BillerudKorsnäs and Viken Skog have formed a joint venture to explore the feasibility of pulp production, biogas production and carbon capture solutions.

In other locations, Silva Green Fuel recently completed a demonstration plant for biofuel made from forest feedstock, and Biozin is developing biocrude from forest raw materials and sawmill residuals. The project got a boost when Biozin’s parent company, Bergene Holm, signed a contribution agreement with Shell.

Carrying on the wood construction legacy

Norwegians have been wood construction experts for centuries. Just look at the Vikings’ wooden ships and the medieval stave churches that are still standing. Today, Norwegian engineers, designers and architects are drawing on this legacy to move us into the green transition.

“It’s also notable that Norway has the least expensive wood in Europe,” Sørlie adds.

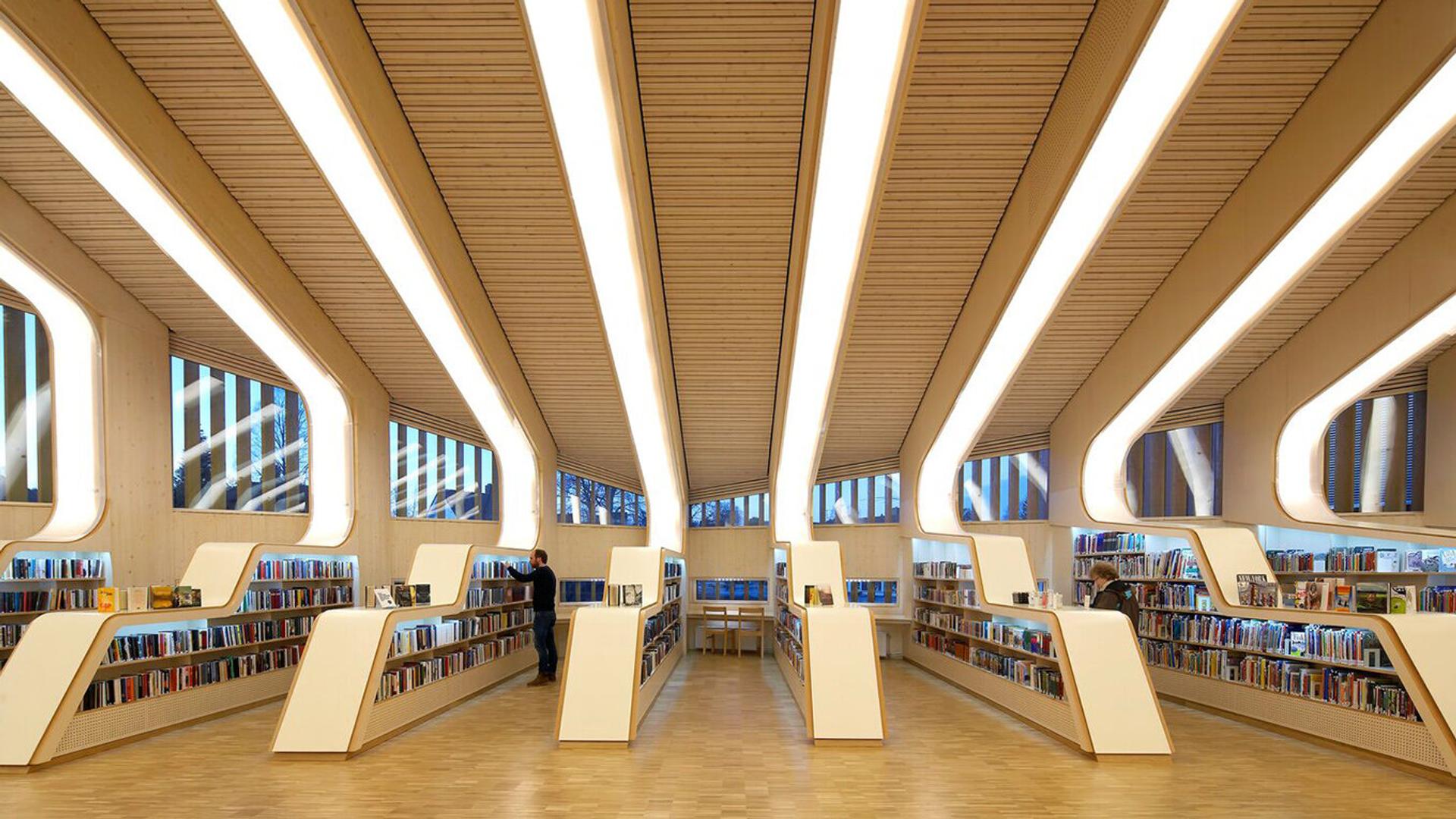

Wood has a softer side as well, according to Siv Helene Stangeland of Helen & Hard Architects, designer of the stunning Vennesla Library and award-winning The Financial Park. “Timber is an organic material that connects us to nature and has a tactile quality. It smells good, it provides very good acoustics in the room, and it calms us down,” she explains.

The world’s tallest wood building is found in Norway as well. Known as Mjøstårnet, it is an example of the greening of the construction industry, as it was built with local resources, local suppliers and sustainable wood materials.

“Wood can replace steel and concrete steel with a much smaller carbon footprint. Plus, forests act as a carbon sink, and the buildings store CO₂. When built properly, wooden structures can withstand various effects of climate change, such as hurricanes and torrential rains.”

Hans Asbjørn K. Sørlie

Director of Forestry & Environment, Norwegian Forest Owners’ Federation

Full wood ecosystem support

The Norwegian government’s Green Platform Initiative provides funding for companies and research institutes engaged in green growth. Projects such as circWOOD have received millions of kroner to establish a circular value chain for wood, and various public-private clusters, such as the WoodWorks! Cluster and the Norwegian Wood Cluster, facilitate synergies within the forestry and wood sector.

As Aaberg of Treklygen points out, broad-based support is crucial for success. “Industry must work together with the community. You can’t just stick a biofuel plant on any plot of land and expect it to thrive. There must be a public-private ecosystem around it. Norwegians excel at this, and we see the benefits at Treklyngen,” he concludes.