Norway’s submarine cable network provides world-class connectivity

Rønning is the head of the Norwegian Data Centre Industry Association under the umbrella of ICT Norway. He is the main author of a recently published white paper detailing the evolution of the fibre optic cable network connecting Norway to Europe and beyond. Being on the geographical fringe of Europe, Norway has historically lagged somewhat behind its neighbours when it comes to connectivity to the data highways running through mainland Europe.

Despite this connectivity disadvantage, Norway has attracted significant investment in data centres, due to the country’s access to affordable clean hydropower.

A recent flourishing of submarine fibre optic cables, however, has provided Norway with direct, secure and fast links to the main data hubs on the continent. This, in turn, opens the door for even more data centres and other cloud computing operations.

“Norway is now on a par with – and occasionally exceeds – the other Nordic countries in terms of connectivity.”

Bjørn Rønning

Norwegian Data Centre Industry Association

Submarine cable networks for faster, safer data traffic

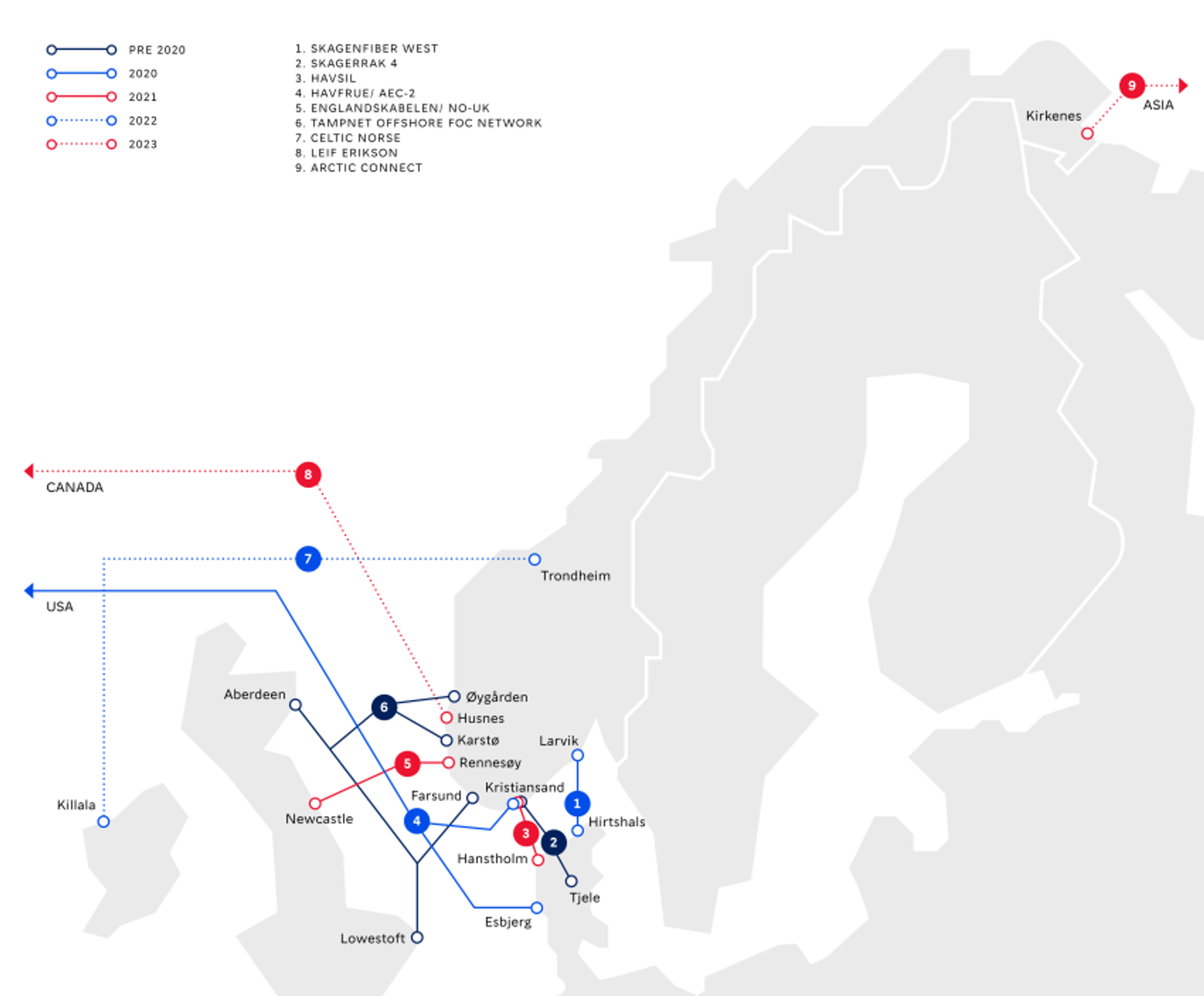

High-capacity fibre cables are required to move vast quantities of data over large distances. Where Norway previously only had a few such undersea cables providing connections to the European mainland, the country now boasts an extensive network providing direct links between Norwegian coastal cities and European data hubs. There are four such undersea cable systems in place already, and two more are under construction, providing new and improved connections to strategic data locations in the UK and Europe.

How exactly does this submarine cable network contribute to connectivity? Rønning explains:

“Norway used to have a latency disadvantage because traffic from Norway had to go east via Sweden to get to Europe. The expansion of the submarine cable network has given a more direct line to European data hubs, removing this disadvantage. In some cases it even gives Norwegian locations a latency edge compared to its Nordic neighbours.”

Apart from latency improvements, the second major transformation has to do with the integrity and safety of the system itself.

“Fibre cables get disrupted all the time – on land the culprit is usually digging or building projects, while undersea cables are vulnerable to trawlers, anchor drops and geological movements,” Rønning says. “It is impossible to put a precise value on the data and transactions going through these undersea cables, but it is safe to say that every second of interrupted operations results in staggering loss for the companies involved.”

“So companies looking for data centre and cloud service sites will always choose locations providing alternative routes that serve as backup in case of interruption. Tech giants like Google and Facebook, for example, use the term “quadversity”, strongly favouring data locations where they have no less than four different pathways. This is another reason why these new cables matter so much.”

High demand for data centres

According to Rønning, it is easy to identify the driving force behind Norway’s submarine cable expansion.

“It is primarily the Norwegian data centre industry,” he says.

Simply put, an increasingly digital economy needs data centres to function, creating a competitive market for data centre sites. Norway has become an attractive prospect for data centre investors, as the country’s unrivalled access to clean and affordable energy can feed power-hungry data centres, keeping costs low and the carbon footprint small.

Several Norwegian data carriers have seized this opportunity with both hands. One of these is Tampnet Carrier, whose North Sea submarine optical network was originally built to support oil and gas platforms. As the potential in the Norwegian data centre industry became apparent, Tampnet Carrier has expanded its fibre network. The company now provides direct connections between a multitude of locations in Western Norway and landing points in Denmark, the Netherlands and the UK.

“In 2016, we identified a great potential to utilise our significant network capacity to serve customers in both Norway, the UK and Europe with first-class connectivity. That is why we established Tampnet Carrier. Because of the diversity of our routes and the stability of the network, we have grown significantly,” says Cato Lammenes, managing director of international carrier operations.

Case in point: in 2020 alone, Tampnet Carrier increased its delivery of data traffic in and out of Norway by over 90 per cent.

“We see a growing demand in Norway, with data centre clusters being established many places in Norway, and we are continuously expanding our network.”

Cato Lammenes

Tampnet Carrier

Direct undersea cable connection between Europe and Asia

In addition to the cables already in place and under construction, three more projects are being planned. The Celtic Norse cable will connect Trondheim in Central Norway to Killala, Ireland. The Leif Erikson cable, operated by Bulk Infrastructure, will run between Husnes in Western Norway and Goose Bay, Canada. And finally, the Arctic Connect cable will run between Kirkenes at the northernmost tip of Norway and Hokkaido, Japan.

“This is huge. Arctic Connect will make Norway the fastest waypoint between Europe and Asia,” says Bjørn Rønning of the Norwegian Data Centre Industry Association.

Norwegian data centre industry ready to meet anticipated data demand

“Another positive consequence of these cable expansions is that it opens up larger parts of the country to data centres. Data centres that are very latency-sensitive are no longer confined to just Oslo or Kristiansand, but have far greater flexibility in terms of location,” Rønning says.

Nevertheless, there is no guarantee that all new fibre optic cables will be used at full capacity.

“It’s an age-old dilemma: should we build to order, or should we build in anticipation of a future need? There’s no doubt that all these cable projects involve risks.”

According to Benedicte Fasmer Waaler, investment manager for data centres at Invest in Norway - the Official Investment Promotion Agency of Norway - there is little doubt that the new undersea cables will be put to good use.

“I believe the Norwegian data centre industry is well positioned for significant growth in the years to come,” she says.

“And a resilient fibre network is important not only for data centres, but for all sectors of society and the economy,” she adds. “During the pandemic, for instance, we have all seen how important a robust digital infrastructure is for society – both during and after working hours.”