Norway emerging as future port hub for European offshore wind

Published 9 Apr 2024 (updated 29 Oct 2025) · 5 min read

An offshore wind farm makes an impressive sight. Massive wind turbines, blades rotating, tower over a vast, often turbulent sea.

Far less flashy, but equally crucial, are the port facilities on shore, where wind farm assembly and installation take place. One is not possible without the other.

According to a recent study, European targets for offshore wind installed capacity for 2030 cannot be met without a huge expansion of dedicated port infrastructure. Norway has recognised this, stepping forward as a leader in offshore wind port development and expansion. Until now, though, Norway’s role has been a well-kept secret.

“Norway can be the answer to the port capacity problem in Europe,” states Astrid Green, Business Development Manager at the Norwegian Offshore Wind industry cluster. “Now we need to get the word out.”

“Norway has ideal conditions for port infrastructure.”

Turid Storhaug

CTO, Global Ocean Technology

Ideal port conditions for floating and fixed offshore wind

Norway is blessed with 103 000 km of coastline, the second longest in the world. This, along with its strong maritime sector, gives Norway a natural advantage when it comes to ports. Today, as offshore wind grows, Norwegian ports are gaining attention as optimal sites for assembly and installation of offshore wind turbines and other assets.

“Norway has ideal conditions for port infrastructure,” states Turid Storhaug, CTO at Global Ocean Technology, which owns and operates Windport, a port located on Norway’s southern tip whose ambition is to become a net-zero emission port. “In our fjords, we have deep waters, sheltered areas and access to large quay fronts that sit on solid rock. On the south coast, the sea has no ice in the winter, low tidal variations and no sand banks.”

The country’s geographical diversity supports both floating and fixed structures. For nearly three decades, Norway’s southern coast has been involved in the fixed market in the North Sea Basin. Now, Norway’s western and northern regions aim to exploit the potential of the Norwegian Sea with depths from 50 to 1 000 metres.

“Windport can serve both the bottom-fixed and floating markets, which are in different stages of development. Fixed is a mature market, while floating is a new market that will see growth in the late 2020s and early 2030s,” says Storhaug. To illustrate, Windport is targeting large bottom-fixed wind farms in the Sørlige Nordsjø II area, but is also preparing for upcoming floating wind projects.

“Norway can be the answer to the port capacity problem in Europe.”

Astrid Green

Business Development Manager, Norwegian Offshore Wind

Demand for ports increases with offshore wind capacity

In 2022, Norway’s port infrastructure got a boost when the government announced its aim to allocate 30 GW of offshore wind capacity by 2040. This marks a significant increase in the government’s support for the future of offshore wind. Most of the sites to be auctioned off are best suited for floating wind.

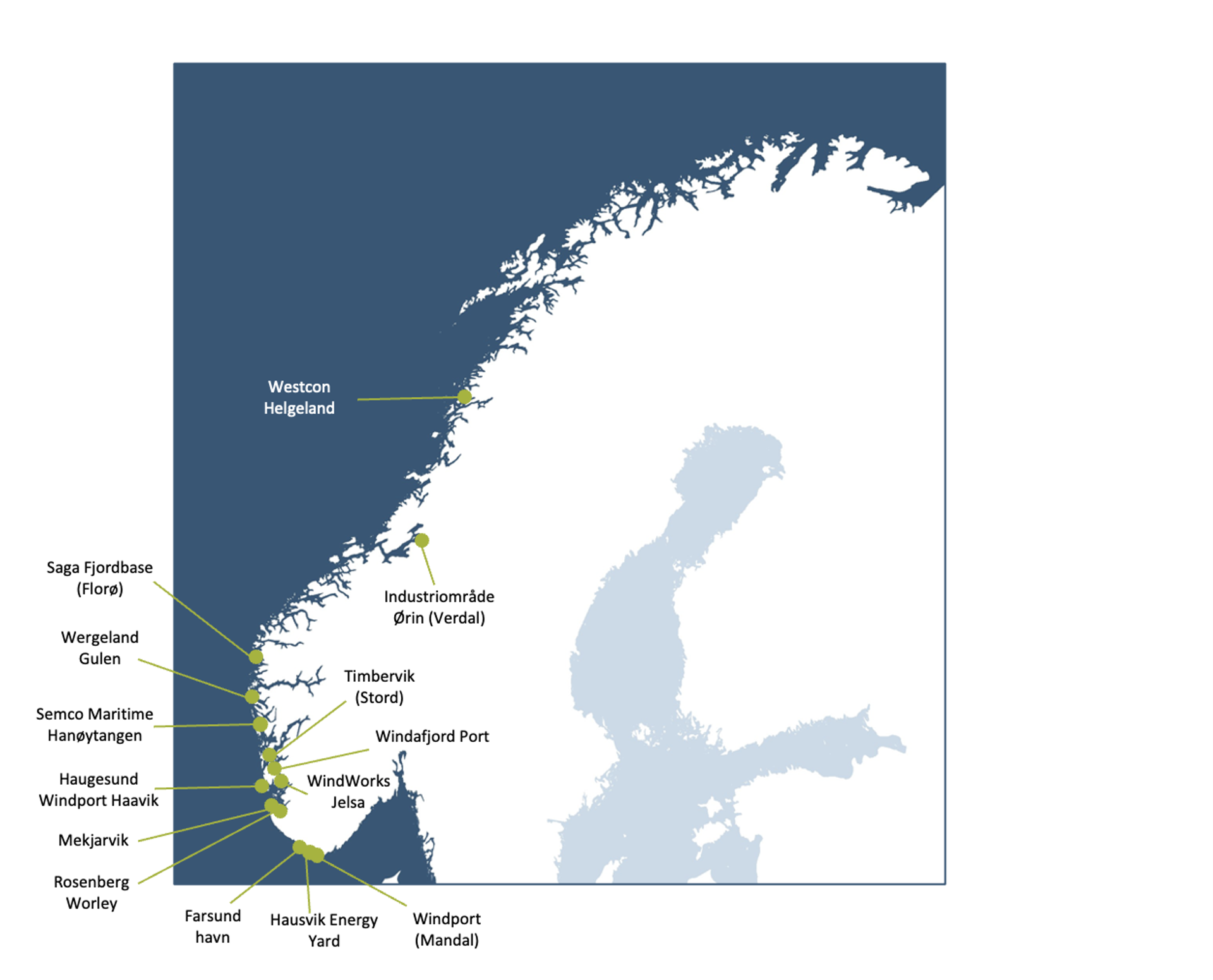

A new report from Menon Economics puts hard numbers on this. Commissioned by Norwegian Offshore Wind, among others, the report is the first of its kind to analyse the potential of Norwegian assembly and installation ports in offshore wind up to 2030. The study identified 14 such ports with plans to facilitate projects for offshore wind farms by 2030, indicating significant potential for employment and value creation.

Norwegian ports to benefit from offshore wind expansion

The report finds that Norwegian ports investing in offshore wind can generate NOK 8.4 billion in annual value. Collectively, these ports aim to achieve an annual installation and assembly capacity of 5 GW by 2030, equivalent to approximately 350 wind turbines annually. The analysis finds that offshore wind will become a significant export industry for the ports, particularly for projects close to Norway.

One of the largest Norwegian actors in this area is the NorSea Group, whose ports and supply bases dot Norway’s coastline and who is a strategic partner to the Ventyr Nordsjø II consortium, consisting of Parkwind and Ingka Investments, which recently won the first auction for the allocation of a project area in Sørlige Nordsjø II.

“Everything starts and finishes with an efficient port.”

John E. Stangeland

CEO, NorSea Group

“In NorSea we are proud and excited to be a partner in this winning project. We are looking forward to supporting the consortium with NorSea’s experience gained through six decades of offshore industry,” says CEO John E. Stangeland.

“Everything starts and finishes with an efficient port,” he elaborates, noting that floating offshore wind faces many challenges, including inflation, supply chain capacity, large-scale serial production capabilities and lack of suitable port infrastructure.

Norwegian ports have an advantage vis-à-vis offshore wind. While most ports in Europe are fully booked by other industries, existing Norwegian ports can be expanded to include offshore wind activity. Also unlike the rest of Europe, Norway has land readily available for new port development.

“Offshore wind structures are getting so large that they must be built and assembled at the quayside. This will require quays of sufficient size and strength to handle up to 25 MG turbines weighing 1 000 metric tons each and foundations the size of an oil rig,” explains Stangeland.

“Norway can deliver on this, as long as the government provides funding for port infrastructure. We cannot do this alone,” he adds.

Norwegian ports collaborate to create synergies

To pull this off, Norwegians will need to draw on their strong tradition of cooperation. As Stangeland suggests, development of costly, high-risk floating wind will require a joint effort between industry, government and academia. To help to achieve this, Norwegian Offshore Wind has formed a working group on offshore wind ports, headed by Turid Storhaug, which will explore ways ports can work together to create synergies and provide industry input to the Norwegian government.

“Norwegian ports need to join forces to gain visibility abroad. We need to show the unique capabilities we have in Norway when it comes to port infrastructure, a highly skilled workforce and a well-established supply industry,” concludes Storhaug.