Marine science: tremendous potential for machine learning

Machine learning is a branch of artificial intelligence (AI). It enables computer algorithms to learn and improve without being programmed.

In two recent articles, three researchers at the Institute of Marine Research (IMR) – Nils Olav Handegard, Ketil Malde and Howard Browman – explore the possibilities offered by machine learning for marine research.

“Machine learning can improve and expand the scope of marine research by identifying underlying patterns and links,” says Howard Browman.

He believes that the technology is particularly useful for dealing with large quantities of data that are difficult to handle.

Machine learning: increasing accuracy

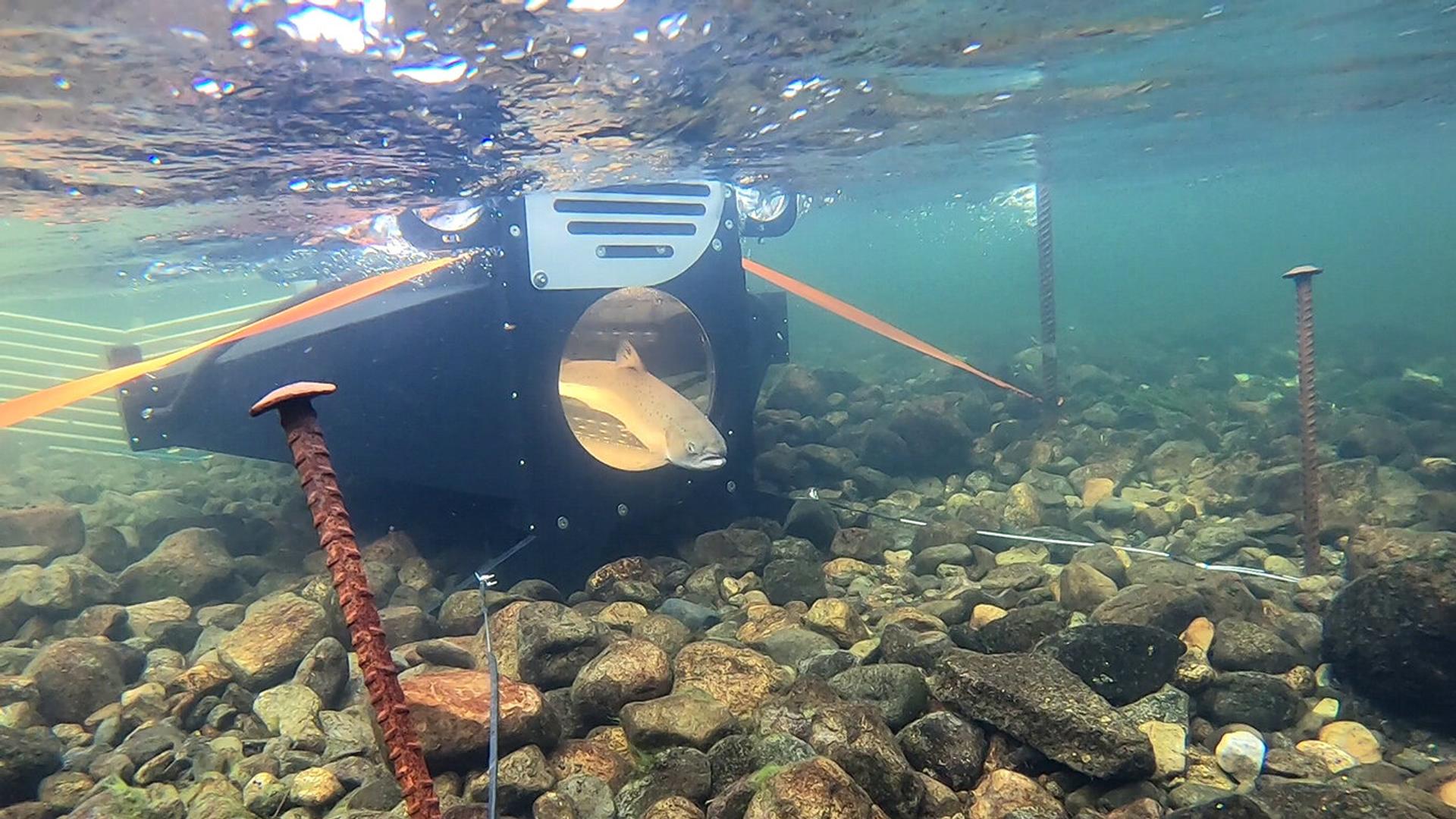

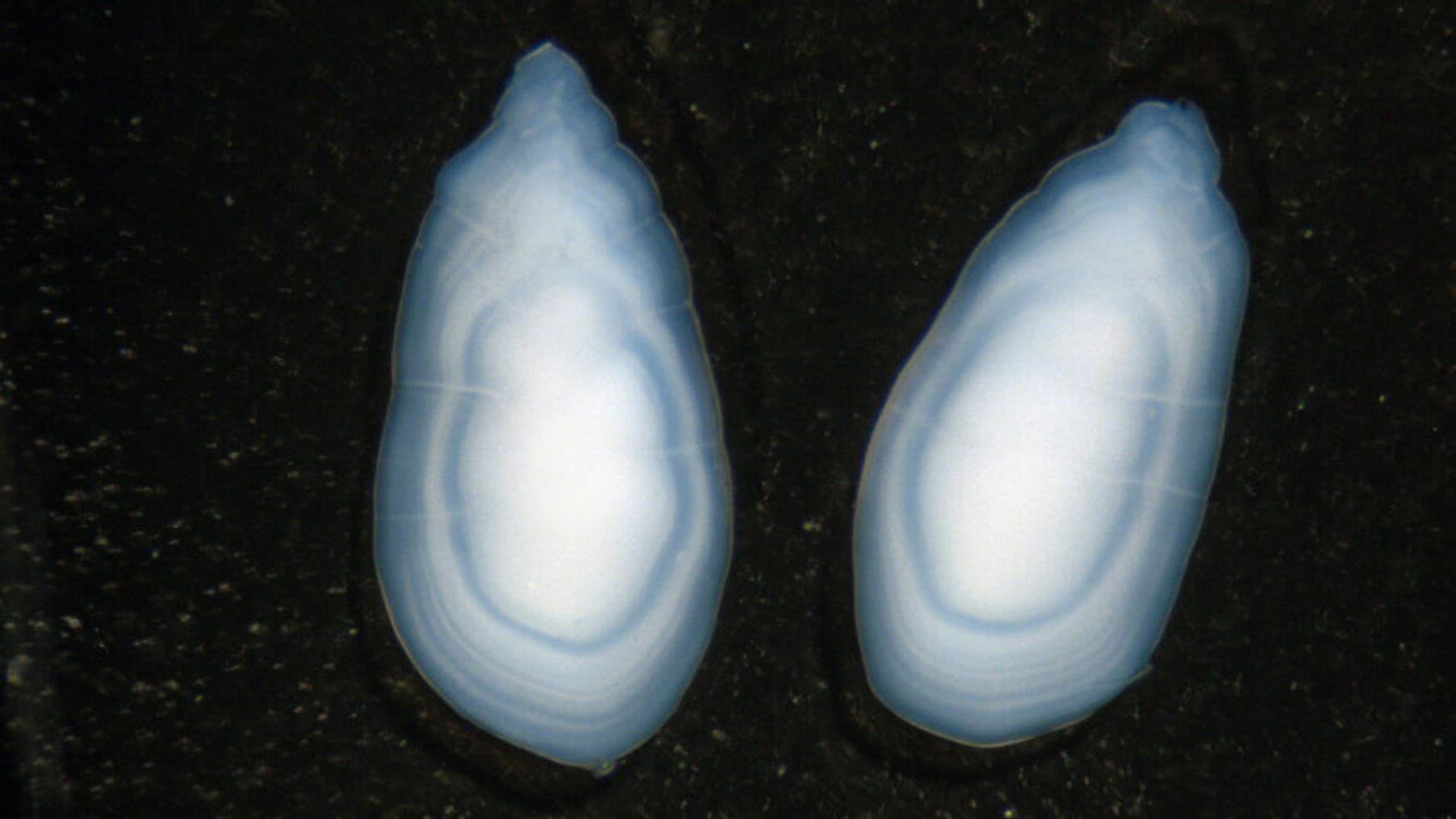

Researchers at the IMR have recently used machine learning to analyse otoliths and fish scales. Otoliths are found in the ears of fish. Together with fish scales, they tell us a great deal about the ages and life stories of the fish – much like tree rings.

Machine learning has proven to be an effective tool, with accuracy sometimes matching that of human analysts.

“Although you ideally want that kind of accuracy, there are also many applications in more limited scenarios,” explains Nils Olav Handegard.

He points out that using machine learning to weed out irrelevant data can be just as important. Partly because it saves time, but also because it makes the scientists' work more rewarding.

“By reducing the number of trivial routine tasks, it allows the human experts to concentrate on more interesting and rewarding work,” says Ketil Malde.

But there are still some challenges to overcome.

“The technology has enormous potential, but you need large quantities of data to ‘train’ the models. Often there is more work involved in collecting and organising the data than in developing the system itself,” Malde says.

“In order to exploit the work that has been done, we must start using these systems in our research and advisory activities. That requires good cooperation across the institute,” he points out.

Machine learning algorithms: training to handle large data sets

The IMR researchers have drawn inspiration from the structure and workings of the human brain to find the best way to train algorithms. With properly trained algorithms, marine scientists will be able to feed large data sets into the computer and discover patterns that would otherwise have remained hidden or hard to detect.

“This technique can be used to find patterns in large volumes of historical acoustic data, which is difficult to do manually,” says Handegard.

Thanks to technological progress and greater computing power, it has become cheaper to build large data collections. Consequently, the use of machine learning will only increase, concludes Malde.

References

Ketil Malde, Nils Olav Handegard, Line Eikvil, Arnt-Børre Salberg: “Machine intelligence and the data-driven future of marine science”. ICES Journal of Marine Science, Volume 77, Issue 4, July-August 2020, Pages 1274–1285 Link: https://doi.org/10.1093/icesjms/fsz057

Cigdem Beyan, Howard I Browman: “Setting the stage for the machine intelligence era in marine science”. ICES Journal of Marine Science, Volume 77, Issue 4, July-August 2020, Pages 1267–1273. Link: https://doi.org/10.1093/icesjms/fsaa084

The original version of this article was published on the Institute of Marine Research website on 12 August 2020. Author: Liv Eva