Edtech helps pupils during the coronavirus crisis

Schools all over the world have been forced to make dramatic changes in order to prevent the spread of coronavirus.

Norwegian companies are helping teachers and students to cope by offering online quizzes, eBooks and new, digital teaching methods. Some companies have seen the number of users increase more than tenfold.

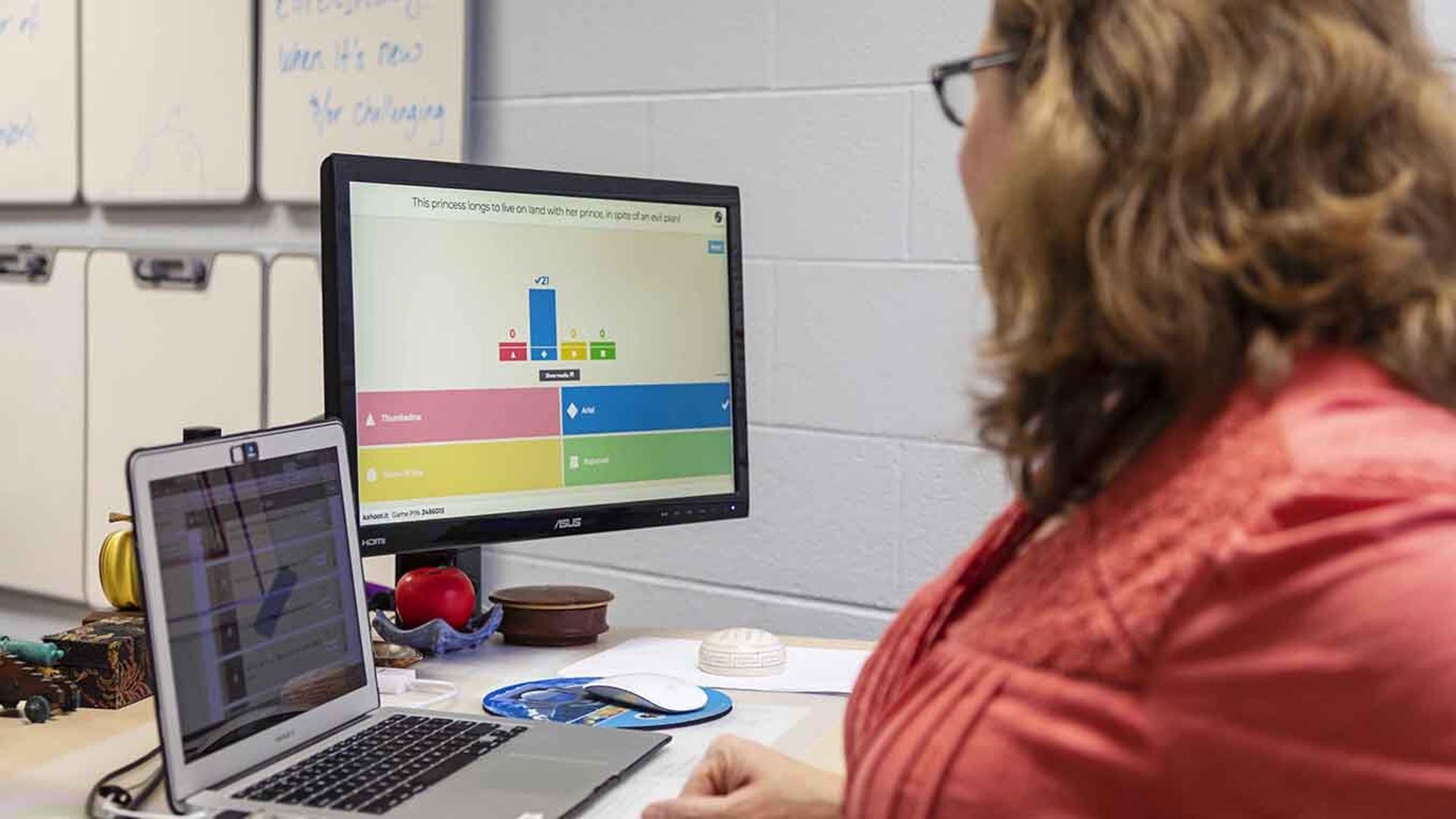

Kahoot!’s quick response

As a game-based learning platform, Kahoot! is a Norwegian success story: the educational tool is used by more than six million teachers in over 150 countries. That has proven useful when pupils are not allowed to go to school or are taking part in hybrid learning.

“Engaging pupils is more important than ever during the coronavirus crisis. We are committed to helping teachers to use Kahoot! for social and emotional learning. When pupils take part in a positive learning environment, they can help each other, play on teams, and cooperate, thereby developing themselves,” says Sean D’Arcy, SVP Head of Marketing at Kahoot!

In 2020, the company provided schools and higher education institutions affected by the coronavirus situation with free access to what was then called Kahoot! Premium until they reopened. The company has now developed the Kahoot! for schools distance learning platform, for which schools can sign up for free.

“We want teachers to have everything they need to follow pupils’ progress and benefit from advanced analytics for teaching. Kahoot! allows them to pose open questions and set up tasks for pupils to solve at any time. This way, pupils can work on tasks on their own,” explains D’Arcy.

According to D’Arcy, infrastructure and digital competency were key factors to Norway’s success with distance learning during the coronavirus crisis.

Home schooling with Lesemester

Monica Berntsen, a teacher at the Norwegian school in Rojales, Spain, does not take the digital advances made by the Norwegian school system for granted.

She has been an advocate of digital teaching tools for many years and often uses the Lesemester online service in her own teaching. The tool provides access to hundreds of eBooks for children and young people and has many useful teaching functions. Among other things, pupils can participate in quizzes, earn points for reading progress and listen to assigned books as audiobooks.

Unsurprisingly, Lesemester experienced tremendous growth when schools were closed. The company used to have 1 000 to 2 000 daily users distributed among some 250 schools. Once distance learning became necessary in spring 2020, the numbers climbed to 16 000 to 18 000 users in over 2 000 schools.

“One challenge of ordinary classroom teaching is that we seldom have enough books for all the pupils and not everyone experiences the same feeling of accomplishment when reading. In that sense Lesemester is an ingenious tool. All the pupils read the same book, earn points and get reading buddies through the service.”

Since its launch in 2017, Lesemester has made a large selection of eBooks available in the three official written standards in Norway: Bokmål, Nynorsk and Sámi. A number of English books adapted for children and young people have also made their way onto the digital bookshelves. Both fiction and textbooks are available for different reading levels.

“Lesemester is a portal that motivates pupils to read a lot and often. The service can give teachers good insight into reading speed. They can see where pupils stumble and can monitor reading comprehension with quizzes,” says Rune Vindenes, CEO at Lesemester.

Monica Berntsen is pleased that digital tools like these are used on a fairly wide scale in Norway.

“I can continue to give the children reading assignments and be sure that all of them have access to the books. So reading lessons haven’t fallen by the wayside during the crisis. The future is digital,” she asserts.

Motivational edtech from Kikora

From his home office in spring 2020, Eivind Ljones Berge faced an unusual problem for a math teacher: he had to wait to assign his pupils math problems on the online service Kikora to stop them from completing them before class.

In a 2020 interview, Ljones Berge – a Year 8 form teacher and mathematics coordinator at Ellingsrud school in Oslo – says: “Today my pupils have English until 11:00 and will have math from 12:00. If I had posted their math assignment on Kikora yesterday, a lot of them would have already solved the problems.”

Kikora is now being used by over 250 000 Norwegian pupils who are solving over 1 million math problems a day – a doubling from before the COVID-19 pandemic. Kikora’s key to success is that it reflects what is perhaps the most important aspect of classroom teaching: when solving math problems, the process is just as important as the answer.

According to Ljones Berge, the main reason Kikora engages pupils so much is that it motivates them with “rewards” such as virtual trophies for solving math problems. Pupils get a feeling of accomplishment that is hard to achieve outside a physical classroom.

“This is something they’re used to from digital games and it makes them want to solve the problems. I find that many pupils want to ‘beat’ the textbook,” he says.

Anders Baumberger, Chief Editor at Kikora, stresses that the service is not designed to replace traditional teaching. Rather, it is a tool to encourage social interaction. Baumberger believes that more and more people will become aware of the value of digital teaching tools.

“It will be interesting to see whether the coronavirus situation will speed up development, also in areas where digitalisation hasn’t come that far. I expect that many German schools, for example, are being forced to used digital solutions that they haven’t used before. I hope they continue to incorporate these into more balanced teaching which draws on the best of two worlds,” he says.

No Isolation robot lends an ear

As pupils once again flood the classroom, there is hope that more teachers in the school system will continue to use the digital tools they learned to use in distance learning.

No one knows how long it will take for life to return to normal – and it may take much longer for a number of children.

“Thousands of children have health problems, such as a compromised immune system. They won’t be able to return to their normal lives as long as there is a danger of infection,” says Hans Fredrik Vestneshagen, Relations Manager at No Isolation.

The technology company has created AV1, a robot that allows children with long-term illness to participate in school and other social arenas. Vestneshagen is responsible for No Isolation’s activities in German schools, with three large-scale projects underway in Berlin, Hamburg and Kiel. He says that both pupils and teachers have had excellent experiences using AV1 in the classroom.

“German schools lag a bit behind Norwegian schools when it comes to digitalisation, but they are extremely positive to AV1. Together with the local school systems we have thoroughly tested the technical aspects of the robot, and we have used a lot of time with teachers and parents to help them to understand how it works,” says Vestneshagen.

AV1 works like this: the child logs on to an app, allowing them to see, hear and speak to their classmates via a little white robot placed in the classroom. Using the intuitive app, the child can raise their hand and even express happiness and wonder.

“When the majority of kids are back in class, AV1 can give those who still have to stay home a physical presence. This way they too can come back to school, even if it’s not in person,” says Anna Holm Heide, Chief Communications Officer at No Isolation.

The company has used considerable time and resources to safeguard personal security and privacy. The only person allowed to connect to the robot is the pupil at home, the video stream cannot be recorded, and all data is encrypted.

When pupils once again fill the classrooms and schoolyards, Heide is certain that they will take good care of their classmate’s little white avatar.

“The robot is the eyes and ears of children who cannot participate in person. When things return to normal, we mustn’t forget those who can’t go back to school,” she says.